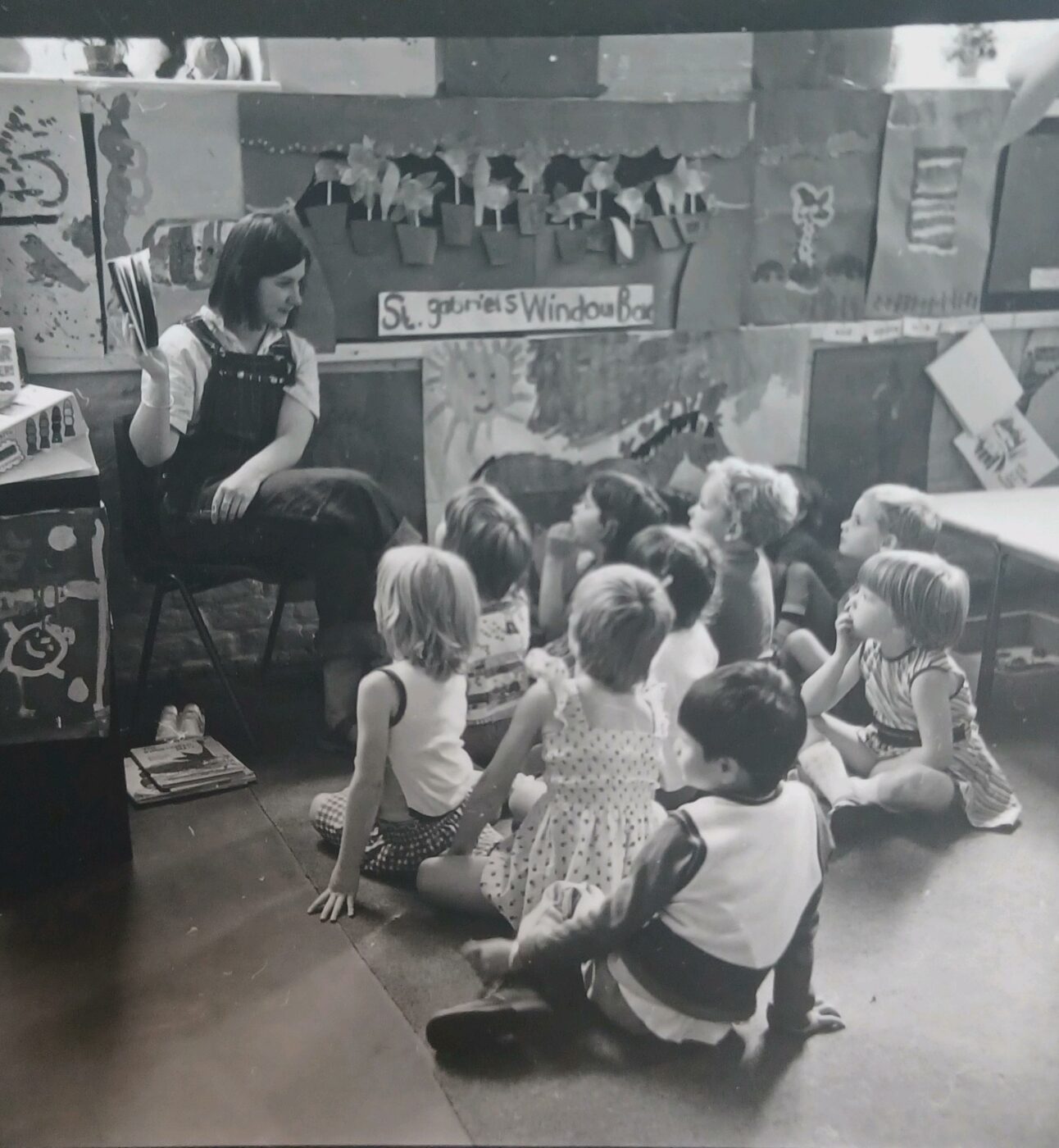

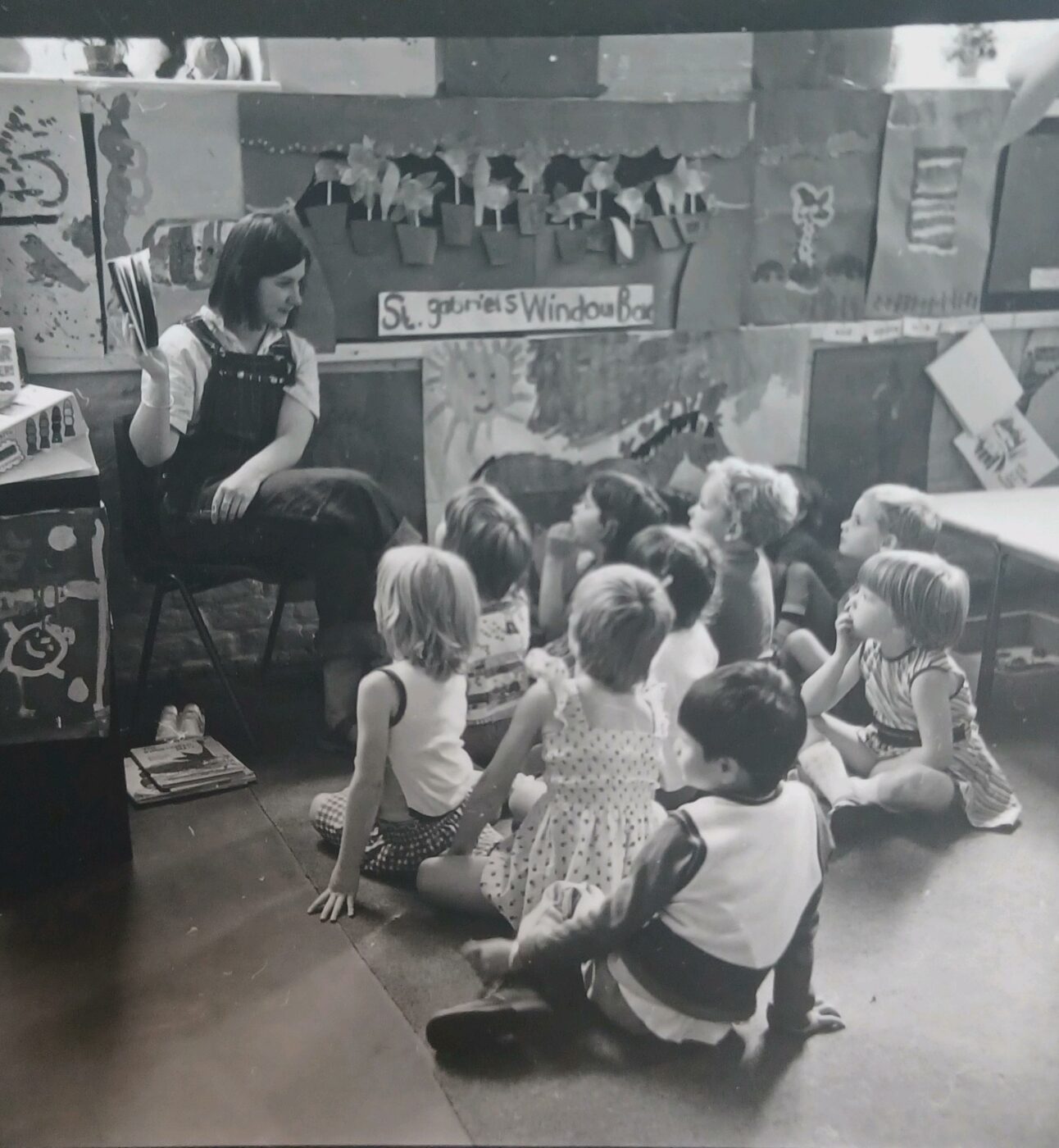

Talking Early Years: Celebrating 120 Years at LEYF

The Year That is 2023 – This year, we are proud to celebrate 120 years of LEYF. It’s been fascinating to reflect back on what has changed over…

September 1st 2011

In the Evening Standard on Tuesday 16th August (Ghetto grammar robs the young of a proper voice) Lindsay Johns touched on something I have been passionate about for a long time; the importance that people and especially those working with young children learn to speak using correct grammar. While Johns focused particularly on young people, his point applies to everyone. According to Johns

“Young people are rendering themselves unintelligible and often unemployable by mainstream adult society”

At LEYF, we have a programme to train young people, many of whom are NEETs to become nursery staff. It is a crucial responsibility in the light of the depressing current statistics which according to a recent report by IPPR tell us that unemployment among NEETs is the highest since 2000 with over a million 16 to 24-year-olds languishing on benefits; up by 18 per cent – in a single year. With this level of unemployment among young people and the battle for jobs played out on a global scale we have to apply a collective duty to empower our children and give them a fighting chance. As we know that speaking correctly is a success indicator, it is therefore incumbent on each and everyone one of us to do something collectively to challenge the current disgraceful acceptance of the existing situation. It has also huge implications for our next generation. I certainly see evidence of what Johns was commenting on, the increase in text speak and punctuations of innit, yeah right and no I never is very evident among many young staff. Too many staff think this is alright and fail to intervene and staff who can speak using grammar correctly often feel they cannot intervene because they may be seen as patronising. One said to me recently, I just had to say something June and explain that there was no such word as worser!

The Early Years has already got a reputation for attracting the nice but dim and its the reason I have always insisted that we speak grammatically correctly no matter what accent we have. Even last week in the Financial Times Weekend, Rachel Johnson was commenting that she still cannot believe she ended up at Oxford without the support of her school because in truth she was just suitable to be a beautician or a nursery nurse. So the stereotype is alive and kicking. However, we will simply reinforce the stereotype that staff working in the Early Years are unintelligent if we fail to challenge and insist on staff thinking about what they say and how they say it. Johns is quite right how you speak and the range of vocabulary you use determines how people see you and measure your intelligence. Language and communication is a vital indicator of success in this society, one we start measuring from the time the child is two years old; so why should it be different later on?

When I first started insisting that we had to have a stand on this, many years ago, I was called a crank, told it was not my business to correct staff. I was incensed as I could see that we were disempowering young people by not setting expectations and trying to fool them into believing that street talk was acceptable. It was compounded by lazy marking attitudes from Awarding Bodies which told us not to focus on grammar. Now we have an epidemic with scary consequences for the next generation.

At LEYF, I have waged an internal war for staff to speak grammatically correctly. It grieves me to hear grown adults unable to use the verb “to be” correctly, rely on slang and use double negatives randomly. They tell me it’s their accent or they way they learned to speak. It’s none of those things but a combination of laziness and arrogance where people think speaking like an infant and using the rich English language in a limited way is satisfactory.

Many children are sent to nurseries to learn to speak English. They often come from poor backgrounds where their parents have English as a second language. Therefore, for many children they have started life with a disadvantage. Our job is to help overcome this and get them on the road to success. One way to do that is to help them achieve a competent grasp of the language and offer them the chance to develop a broad vocabulary. Language is power and the ability to communicate has a huge importance and with it comes the perception about intelligence. James Heckman, the Nobel prize-winning economist conducted much research on the success factors for children. Unsurprisingly, their ability to communicate and the richness of the communication was critical. He found that by three years old a child from a poor background may have acquired up to 500 words while a child from a professional home will have achieved 1100. That gap was almost impossible to reduce and the impact for many was life long.

So if we continue to allow the acceptance of infantile speak as the norm among young children we simply take ten steps backwards. Those trendy media presenters who try to do street talk to sound cool are mostly well-educated, successful people who can play the game and code switch. This is not an option for many young people and it will certainly not be an option for children taught to speak English by adults who have a limited vocabulary and an inability and unwillingness to speak grammatically correctly.

How dare we think it’s acceptable to fail the next generation by playing the liberal game of pretend equality. We have a duty to ensure all children learn to speak English with a flair and competence that is not just possible but will excite and empower them and enable them to embrace some of the 100,000 words available within the English language. As Johns says

The better they speak the more others especially in positions of power will be inclined to take them seriously. Embracing proper English unlocks intellectual feat we have a duty of linguistic care.

The Year That is 2023 – This year, we are proud to celebrate 120 years of LEYF. It’s been fascinating to reflect back on what has changed over…

We have been raising the issues of childcare funding for over 10 years. It has been so long, I am amazed at how patient I’ve remained – and…

In the beginning of 2022 So here we are. The final blog of 2022. And hey, we’ve managed to get through what has been a year of discontent and foolishness.