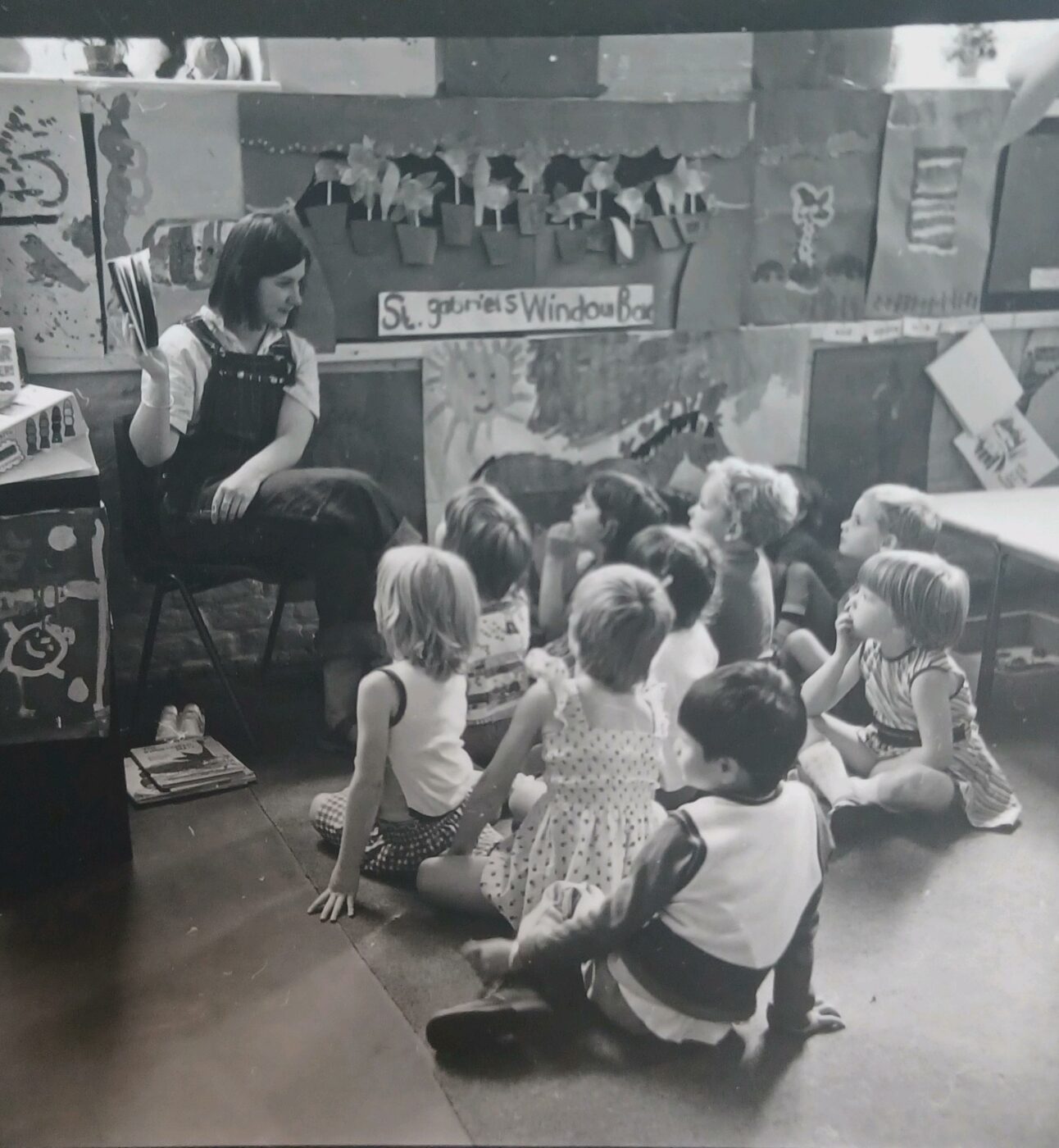

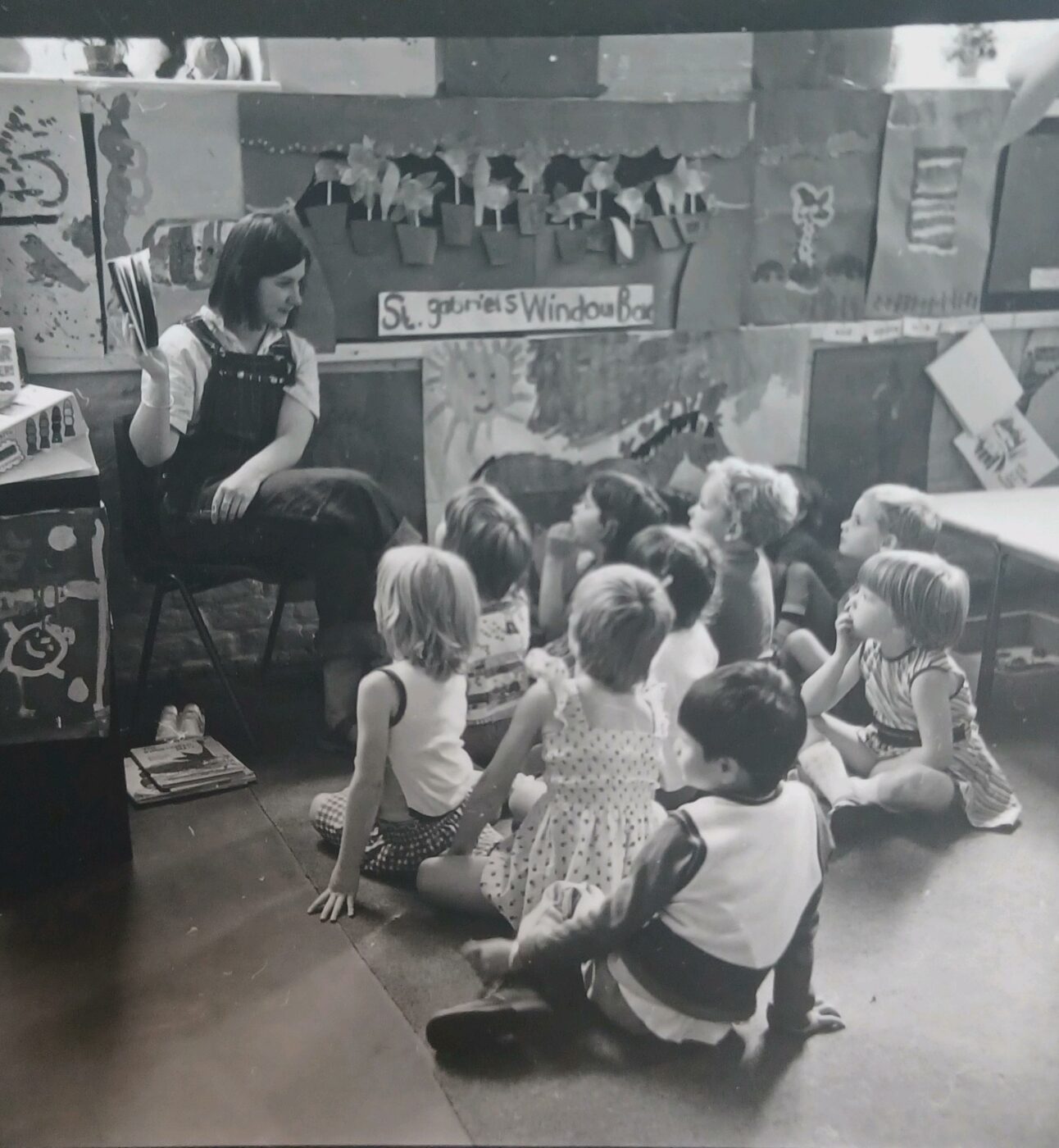

Talking Early Years: Celebrating 120 Years at LEYF

The Year That is 2023 – This year, we are proud to celebrate 120 years of LEYF. It’s been fascinating to reflect back on what has changed over…

May 3rd 2011

This weekend the TV presenters continually referred to the joy and happiness created by the Royal Wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton. Images of laughing people enjoying street parties, smiling at cameras and looking the epitome of happy, connected and positive citizens dominated our TVs.

Why then do we need Action for Happiness, a new organisation set up by Professor Richard Layard, Geoff Mulgan and Dr. Anthony Seldon to challenge the level of unhappiness in the UK, which despite our material comfort is much higher than 50 years ago? They want us to focus on what really makes us happy: healthy relationships and meaningful activities, such as lifelong learning and doing things for others; they want us to reject the dominant culture of materialism and self-obsessed individualism.

I suspect Action for Happiness likes Royal Wedding street parties, however sadly infrequent they may be to make much difference in the long term. What they appear to be more concerned with is the more enduring negative impact of our predilection for regular reality programmes, such as The Only Way isEssex, which although parody materialism and self- obsession also retain a sneaking admiration for both. This particular programme amounts to one hour each week of amusing but vacuous discussion about the key challenges in life: seemingly hair extensions, nails, Botox and men telling women to be serious and “none of your lipstick and nails talk”. It does not take long to realise that Action for Happiness has its work cut out.

Many years ago (1993), Professor Richard Layard gave the Annual Margaret Horn Lecture here at LEYF on the economic value of happiness. As always, it was a thought-provoking lecture, at the end of which I tentatively asked whether we should measure the happiness of children, which to me is the real acid test of a happy society. Some years later, in 2009, Professor Layard produced a report called A Good Childhood, commissioned by the Children’s Society and penned together with Judy Dunn. They noted that children in the UK enjoy good health and can look forward to long lives; they have foreign holidays and a wealth of consumer goods; 90% of children over 11 have their own mobile phone, whilst 80% of 5-16 year olds have their own television. However, despite the level of material goods available to them, children were on the whole more stressed, more violent and less happy than their peers of the seventies or eighties. They concluded that children did not thrive in a consumer culture that promotes ‘excessive individualism’, and in effect children would only truly succeed in a society where people care for each other, promoting each other’s good as well as their own.

When David Cameron became Conservative leader in 2005, he said gauging people’s feelings was one of the central political issues of our time; his mantra was happiness, happiness, happiness. In fact, this is now to be examined as part of the annual Office for National Statistics nationwide Integrated Household Survey.

But what will it tell us about happiness? Will materialism be an issue in this age of austerity? Will self obsession be the type commonly associated with depression and despair? Or will we find an increased level of happiness as people begin to rely more on each other and their own abilities and get a kick out of that? Either way, happiness is squarely on the agenda – and probably a more important issue for the UK right now than a referendum on AV, especially for children.

So what do we know: the UK was last in the UNESCO Well Being report; A Good Childhood told us that our children are miserable and we need to think about them more. We have a Social Mobility strategy to address key issues such as increasing child poverty, a widening gap between rich and poor, expensive childcare and Children Centres under threat. Do we need to hear any more? Probably not.

What we do need is to finally put children at the heart of Government policies. The decisions we make today have to be the basis for creating happiness, not for us but for all of our children. We don’t need any more reports or strategies; we just need to put the child’s voice at the centre and then amplify it, until it rings in our ears and we are forced to listen properly and finally act accordingly. Nelson Mandela summed it up perfectly when he said:

There can be no keener revelation of a society’s soul than the way in which it treats its children.”

The Year That is 2023 – This year, we are proud to celebrate 120 years of LEYF. It’s been fascinating to reflect back on what has changed over…

We have been raising the issues of childcare funding for over 10 years. It has been so long, I am amazed at how patient I’ve remained – and…

In the beginning of 2022 So here we are. The final blog of 2022. And hey, we’ve managed to get through what has been a year of discontent and foolishness.